With the naming of Tropical Storm Vicky on Monday morning, this leaves only one name on the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season list — Wilfred. So what will the next storm be named, after Wilfred?

For what is likely to be only the second time in recorded history, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) will have to use the Greek alphabet for additional storm names.

In 2005, the NHC had to use six letters off the Greek alphabet to account for the record number of storms. Four of those systems reached tropical storm strength (Alpha, Gamma, Delta, and Zeta), while the two other storms reached hurricane strength (Beta and Epsilon). The NHC does not use the letters Q, U, X, Y, and Z because there aren’t enough names to fill those letters.

But will there be more storms?

The 2005 season went into the Greek alphabet. What makes forecasters think 2020 will follow suit?

Atlantic hurricane season officially runs from June 1 through November 30. Statistically speaking, September 10 is the peak of the season. During an average season, we see about three named storms in September, two storms in October and one in November.

Which means that if this were a “normal” hurricane season, we would still likely have a few more storms possible through the end of November. But this year is not a “normal” season. It has been forecast for months to be very active.

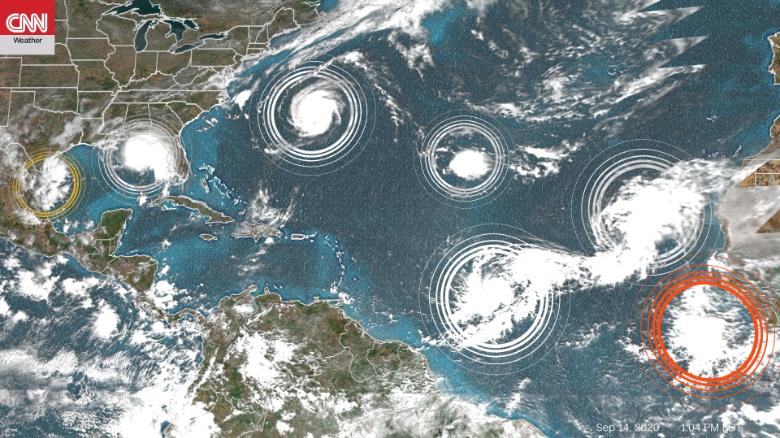

So far this season, we have seen 20 named storms. The average for an entire season is 12.

Back in August, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) updated the hurricane season forecast and called for 19 to 25 named storms. Prior to this, the agency had never forecast up to 25 storms in a season.

Every named storm so far this season, except for three (Arthur, Bertha, and Dolly), set their own personal record for earliest named storm in recorded history.

La Niña is officially here

La Niña is partially to blame for such an active season. Last week, NOAA announced that they issued a La Niña advisory, meaning La Niña conditions are present in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean.

In a typical El Niño phase, much of the Pacific Ocean is characterized by warmer waters, whereas La Niña features a cooling of those same Pacific waters. In the case of hurricanes, La Niña weakens high atmospheric winds, which allows warm air pockets to grow vertically and develop into hurricanes.

It isn’t just the presences of La Niña that is important, but also the lack of El Niño that influences the latter months of the Atlantic hurricane season.

“Typically, what ends Atlantic hurricane seasons is that vertical wind shear gets too strong,” says Phil Klotzbach, a research scientist at Colorado State University.

“So, El Niño, via its impacts on vertical wind shear, has a stronger impact on September and especially October hurricanes than it does on August hurricanes. With La Niña, vertical wind shear tends to be lower, and consequently, we end up with more active late seasons,” Klotzbach said.

There are a lot of comparisons out there to the record-breaking 2005 Atlantic hurricane season because not only is this year’s hurricane season currently on pace to match the number of named storms, it also happened to be a year where La Niña developed in the autumn.

>>>details