While once front and center of U.S. election campaigns, the politically noxious topic of the 19-year-old Guantanamo Bay prison has made little dent on this year’s election cycle.

Yet it still remains open, sparsely populated by alleged terrorists at a high cost to the American taxpayer. And even with the protracted war in Afghanistan winding down as part of a controversial “peace deal” with the Taliban, experts remain skeptical that Gitmo too will be brought to an end.

“The prison holds the most violent people on the planet, and they have become worse since they have been there. If you close it, where are you going to put the prisoners? You can’t bring them back to the U.S. because (then) they are entitled to due process rights,” Kelly Hyman, a political strategist and federal trial attorney told Fox News. “So what do you do with them? You have no foreign country that will take them. Everyone wants to get rid of them, including Trump, but we can’t.”

Retired Air Force attorney, Lt. Col. David Frakt, who was appointed to defend Pakistani Guantanamo detainee Mohammed Jawad in 2009, concurred that while the prison has likely outlived any intelligence-gathering value it may have once had – given that the inmates have longed been removed from the war theater – it remains a political risk whether open or closed.

“There is no end in sight for the detention facilities in Guantanamo; the remaining detainees are likely to be there many more years, potentially for the rest of their lives,” he said bluntly. “There is no (government) willing to take these people into their hands that we can totally trust not to just let them out, and nobody wants to be the president who lets somebody go, and then that person goes and commits a horrible terrorist act.”

EX-CIA CONTRACTOR WHO DEVELOPED CONTROVERSIAL INTERROGATION PROGRAM TESTIFIES AT GUANTANAMO BAY

Defined by high barbed-wire fences, a stretch of bleak mountains, and the odd withered palm tree, the U.S. base by a Cuban minefield remains a bland place. Once a fixture of fodder and intrigue, it now rarely hits news headlines.

A charter plane carrying 143 people and traveling from Cuba to north Florida sits in a river at the end of a runway, Saturday, May 4, 2019 in Jacksonville, Fla. The Boeing 737 arriving at Naval Air Station Jacksonville from Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, with 136 passengers and seven aircrew slid off the runway Friday night into the St. Johns River, a NAS Jacksonville news release said. (AP Photo/Gary McCullough)

The assault of the coronavirus pandemic this year also saw Gitmo fall further from the radar. Trials were halted in February, and movement in and out of the 45-square-mile fortress ground almost to a standstill due to stringent quarantine measures, exacerbating the sense of solitude and of being a forgotten place.

But in recent weeks, a little activity has resumed.

Earlier this month, Stephen F. Keane, a Marine colonel and Camp Pendleton-based senior judge, was appointed military judge in the drawn-out capital punishment trial of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four other prisoners charged with masterminding the Sept. 11 attacks.

Keane’s assignment is seen by foreign policy and legal observers as a vital step forward in resuming pretrial hearings, which were also paused as a result of the sudden retirement of the previous judge, Air Force Col. Douglas K. Watkins.

However, the legal battles remain murky and stretched out. In late August, a federal appeals court ruled that foreign detainees at Guantanamo Bay do not have the right to make due process claims in court, with Judge Neomi Rao stating that “the due process clause may not be invoked by aliens without property or presence in the sovereign territory of the United States.”

The ruling came in rejection of an appeal lodged last year by Abdulsalam Ali Abdulrahman al Hela, a Yemeni businessman who has been held at the U.S. military base since 2004 after being known to have ties to Al Qaeda. It was a further rebuke of a 2008 Supreme Court ruling stipulating that detainees could challenge their imprisonment by filing habeas corpus petitions in federal court.

EX-CIA STATION CHIEF SAYS AMERICA IS ‘A LOT SAFER’ FROM TERRORISM THAN IT WAS FOUR YEARS AGO

The edict was viewed by human rights activists as a significant blow, yet it has further inflamed their push to shutter the facility.

Today, the oldest prisoner there is 73, and the youngest is in his mid-30s. The last known arrival was an Afghan, Muhammed Rahim al-Afghani in 2008, characterized as a “high-level” operative for Al Qaeda.

Some 779 prisoners have churned through the grey concrete of the infamous brig since it first opened in early 2002. Of those, 729 have been either transferred or released to 59 different countries. Afghanistan has absorbed 203 former Gitmo inmates, followed by Saudi Arabia, which has taken 140, Pakistan at 63, and Oman at 30. Egypt, Canada and Denmark have each taken one, and the U.S. has brought in two.

The interior of an unoccupied communal cellblock is seen at Camp VI, a prison used to house detainees at the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay. (Reuters)

Nine have died in custody, the most recent eight years ago, when Adnan Latif, a 31-year-old Yemeni, was reported to have committed suicide.

Of the 40 inmates who remain, five are held in law-of-war detention but recommended for transfer if security conditions are met and seven have been charged in the military commissions’ system. Meanwhile, two have been convicted in that system and three more are proposed for trial. Twenty-three others are being held in indefinite law-of-war detention and are not recommended for transfer.

The highest number of those left are from war-torn Yemen, with 14 Yemeni citizens – most of whom are not recommended for transfer. Pakistan and Saudi Arabia each have four citizens at Gitmo, while Malaysia, Algeria, Libya and Afghanistan have two.

“Since only two Afghans are left, intra-Afghan talks do not seem to matter much for Gitmo,” surmised Ben Friedman, policy director at Defense Priorities. “But if the U.S. war finally ends, it might create political momentum in Washington to resolve the remaining cases and close it.”

Rounding out the numbers are Kenya, Tunisia, Iraq, Somalia, Indonesia, Palestinian Territories, Morocco and “Stateless Rohingya,” with one citizen each in Gitmo.

Those figures have stayed unchanged for two-and-half-years – even though five were recommended for release by a high-level government review process under the Obama administration.

FILE – This Saturday March 1, 2003 photo obtained by The Associated Press shows Khalid Shaikh Mohammad, the alleged Sept. 11 mastermind, shortly after his capture during a raid in Pakistan. On Friday, Aug. 30, 2019, a military judge set Jan. 11, 2021 for the start of the long-stalled war crimes trial of the five men being held at the Guantanamo Bay prison on charges of planning and aiding the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. (AP Photo) (AP)

President Trump, who vowed on the 2016 campaign trail to fill Guantanamo with even more “bad dudes,” hasn’t exactly done that – but under his tenure, only one prisoner has been released. In May 2018, Ahmed al-Darbi was sent back to Saudi Arabia custody following a guilty terrorism plea and some 15-and-a-half years at Gitmo.

Three months earlier, the president signed an executive order affirming Gitmo remains open and instructing the Pentagon to prepare for a potential swell amid ongoing efforts to root out ISIS and Al Qaeda from their strongholds abroad.

For his part, when asked during a Democratic primary debate last December, Joe Biden said Congress has the authority to close the prison, indicating that it was congressional roadblocks that prohibited the Obama administration – where he served as vice president – from making good on promises to immediately put an end to Gitmo.

“First, Congress controls funding and can cut it off tomorrow. Second, we have legislators, and they can pass legislation to have it closed,” Hyman confirmed.

On Jan. 22, 2009, Obama issued an executive order heralding Guantanamo’s cessation within one year – at a time when Democrats held majorities in the House and Senate – but the notion of sending terrorists responsible for 9/11 to be tried on U.S. soil ignited such objection even within his own party that Congress blocked the move through legislation.

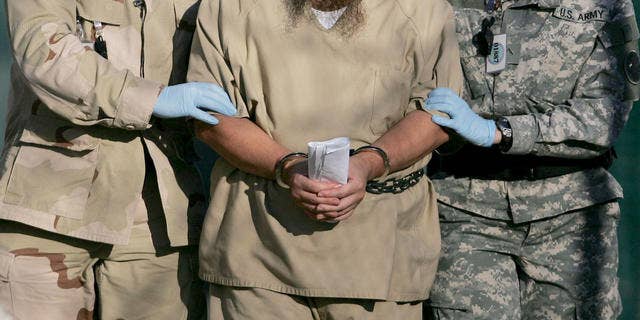

In this photo, reviewed by a U.S. Dept of Defense official, a shackled detainee is transported away from his annual Administrative Review Board hearing with U.S. officials, at Camp Delta detention center, Guantanamo Bay U.S. Naval Base, Cuba, Wednesday, Dec. 6, 2006. Each Guantanamo detainee has the option to participate in his own annual status review hearing which is part of the process for determining if a given detainee will continue to be held for another year. (AP Photo/Brennan Llinsley) (AP)

Nonetheless, in an apparent departure from his previous avowals to keep the facility locked and loaded, Trump last year declared that the U.S. would not utilize Guantanamo as a place to put suspected terrorists “for the next 50 years spending billions and billions of dollars.”

TWO MEN ARRESTED AFTER ALLEGEDLY PLANNING ‘NETFLIX WORTHY’ TERRORIST ATTACK ON US IN SUPPORT OF ISIS

A 2019 tally by the New York Times found that the total operating costs of the isolated facility – from holding the prisoners at an annual expense of $ 13 million each to paying for the U.S. troop presence to guard them to funding construction and the running of war courts – surpassed $ 540 million, making it the most expensive lockup on the planet.

Compounding the Gitmo headache for lawmakers over the years were the revelations of a CIA waterboarding program – called torture by some, and “enhanced interrogation” by others – which came to brutal public light in a 2014 Senate report.

But along with the stain left after the exposure of the once clandestine modus operandi, both condemners and condoners of Gitmo alike are quick to point out that all 40 remaining men are issued halal food and are provided access to cable television, fitness equipment, PlayStations and other means of entertainment. They are allowed to pray together and share mealtimes; some even attend classes to hone creative skills such as art and crafts.

“Daily life is much the same as any prison except the food is better. Detainees have exercise, access to library and crafts, legal reps, and other aspects. Human rights have always been exaggerated since other than a single issue that occurred early on in the fall of ’02, the facility has been run scrupulously,” contended former Special Forces Lt. Col. Gordon Cucullu, author of “Inside Gitmo: The True Story Behind the Myths of Guantanamo Bay.” “During the Bush administration, it became a manufactured issue but faded after Obama failed to close it as he promised.”

Cucullu also observed that there has been an “abysmal” track record of released Gitmo inmates finding their way back to the battlefield.

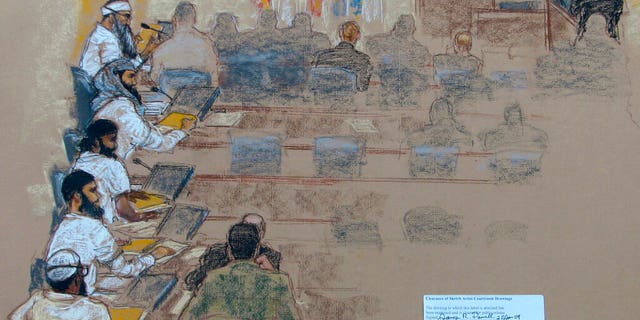

This Wednesday, Jan. 21, 2009 sketch reviewed by the U.S. military, shows, from top left, Khalid Shaikh Mohammad; Walid bin Attash; Ramzi bin al Shibh; Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, also known as Ammar al Baluchi, and Mustafa al Hawsawi attend a hearing at the U.S. Military Commissions court for war crimes at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. On Friday, Aug. 30, 2019, a military judge set Jan. 11, 2021 for the start of the long-stalled war crimes trial of the five men being held at the Guantanamo Bay prison on charges of planning and aiding the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. (AP Photo/Janet Hamlin, Pool) (AP)

Yet 2022 will mark two decades of the detention islet. The next year, 2023, will commemorate 100 years since the United States signed a deal with the newly independent Cuba to lease the land for $ 2,000 in gold per year, which was followed by a formal treaty in 1934 giving the U.S. the green light to lease the land until a mutual departure agreement was reached.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

But there have been no such discussions, and thus, for now, the future of the prison remains unclear.

In August, 150 soldiers belonging to a National Guard police unit in Stillwater, Minn., became the latest troops to embark on a one-year, security-providing deployment to the Bay’s Naval Station.

“There are two reasons Gitmo is so hard to close. One is the military justice system for the inmates has been a fiasco, which has ground on without resolving all the cases,” said Friedman. “Second, there is a political refusal to accept that closure means releasing the unconvicted somewhere, repatriating others, and moving some inmates to U.S. prisons.”

From his perspective, closing down Gitmo is not impossible. But even when it’s out of the media glare, it is still a political hot potato.

“Closing it will require a political compromise,” Friedman added. “And a realization that the expense of running the prison for a few dozen people is vastly in excess of closing it.”

>>>details