Rev. Nelson Johnson remembers marching in Greensboro in 1979 and the protest’s deadly outcome. That’s why he’s been fighting for decades for an apology.

Over 40 years later, the North Carolina city has formally apologized for the deaths of five people during an attack by Ku Klux Klan members and the American Nazi Party.

Recently, Greensboro City Council voted 7-2 to pass a resolution that said the Greensboro Police Department “failed to warn the marchers of their extensive foreknowledge of the racist, violent attack planned against the marchers by members of the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party with the assistance of a paid GPD informant.”

Additionally, the resolution said the police didn’t do anything to stop or arrest the members of the KKK and American Nazi Party as they approached the housing development where the protesters gathered, despite knowing they were armed.

The Greensboro Police Department has declined to comment on the resolution.

The resolution is the latest in efforts by cities and states across the US to acknowledge past tragedies. The shifts in response come as the country reckons with racism and police reform in the wake of nationwide protests and the deaths of Black men and women at the hands of police.

“We have been pushing for this all 40 years, ” Johnson said. He describes the resolution’s passing as a weight off of his shoulders.

“My children have had to grow up on the cultural view in this city that I was an evil person, that I set this up, that I knew it was going to happen and that I wanted a fight with the Klan and so forth,” he said. “Just a lot of nonsense but I think that has cleared up a little bit now and we’re given a little more credit for trying to do the right thing.”

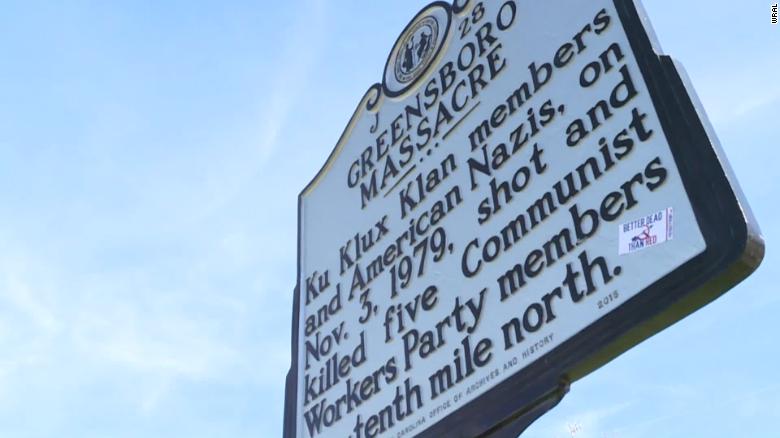

The attack, commonly referred to as the Greensboro Massacre, happened on November 3, 1979, when Communist Workers Party members met for a “Death to the Klan” rally, according to an account of the massacre and its aftermath published by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

The multiracial group of protesters gathered at the center of the Morningside Homes, a housing development in a majority Black neighborhood. Days before the rally, Klansmen and neo-Nazis from across North Carolina heard about the planned demonstration.

As the marchers gathered, the Klansmen followed the demonstrators.

The two groups taunted one another until shots were fired, though according to UNC at Greensboro, it’s unclear where the shots originated. As tensions escalated, Klansmen and neo-Nazis grabbed firearms from their car and began exchanging fire with demonstrators, ultimately killing five.

Cesar Cauce, Dr. James Waller, William Evan Sampson, Sandra Neely Smith and Michael Nathan lost their lives in the massacre.

“This apology is 41 years too late,” Councilwoman Michelle Kennedy said during a virtual City Council meeting on October 6. “On behalf of the 5-year-old kid that I was then and the terror that that sparked for me and the fear that I saw in people’s faces for the first time in ways that as a White woman I will never fully understand, I am sorry for what the city of Greensboro failed to do on that day and for the things that we did.”

“There is nothing in my professional life or really in my adult life that means more to me than saying what we are saying tonight and the only thing I regret is that it didn’t happen 41 years ago,” she said.

Why the resolution says police were complicit

The resolution acknowledges that the Greensboro Police Department knew about the planned attack by the Ku Klux Klan and American Nazi Party but failed to warn the marchers from the Communist Workers Party (CWP).

A police informant told the Klan about the planned rally. The “longtime Klan member and former FBI informant was hired by the police to attend and report on meetings of the Klan and local communist organizations,” according to UNC at Greensboro.

The informant told the police about the Klan’s plans for an armed confrontation, but the resolution says that the police did not in turn warn the CWP about the potential for violence. Police were already wary of the march and the CWP activists.

A day after the incident, warrants were issued for 14 Klansmen and neo-Nazis. Less than a month after the massacre, on December 12, the men “were each charged with four counts of first-degree murder, one count of felony riot, and one count of conspiracy.”

A year later, after a weeklong deadlock at trial, the all-White jury “returned a not guilty verdict on all five murder counts.” In 1983, new charges were filed in the case, but a second trial again led to acquittals.

Eventually, after a trial in a civil suit filed by victims against the City of Greensboro and others, “on June 6, 1985, $ 351,500 was awarded in the wrongful death of Michael Nathan. Smaller amounts were awarded to survivors Tom Clark and Paul Bermanzohnm, while no money was awarded to the estates of Waller, Cauce, Sampson, and Smith,” according to UNC at Greensboro.

Not all were in favor of approving the resolution

Despite the board’s vote earlier this month, two council members did not agree with the apology.

“It was a horrible, horrible day with the tragic loss of life but I do not believe that the City and the Police Department knew of the events that were about to take place on that fateful day,” Councilwoman Marikay Abuzuaiter told CNN in a statement.

Both Abuzuaiter and Councilwoman Nancy Hoffmann voted against the resolution, because they say language in it suggests that police knew about the impending attack and, according to their review of reports regarding the incident, those are unsubstantiated claims.

“I find myself in the difficult, indeed impossible, position this evening of being in support of a formal Resolution of Apology but unable to support this resolution based on its language indicting the City of Greensboro Police Department and other City personnel for an event that occurred 41 years ago and one which has been exhaustively investigated and vetted,” Hoffmann said during last week’s meeting and in a statement to CNN.

After reviewing three investigations and reports from 1980, Hoffmann said, “neither report found evidence of willful or wanton conduct by the officers of the GPD prior to the actual altercations between the opposing parties.”

“I wish this event had never occurred; we always grieve the loss of life,” she said. “But I find nothing in the contemporaneous reporting of this event that convinces me of collusion or malicious action or inaction on the part of the Greensboro Police Department or City personnel.”

“I unequivocally reject the thinking that while this Resolution indicts a police department of 41 years ago, it does not impact our current Police Department and Chief. The words of this Resolution continue to place our Police Department and our City under a cloud of negativity as we strive to continue moving forward and making progress in all areas in a year that has been difficult and challenging.”

A continuous 40-year push, but why now?

In 2009, a Greensboro City Council statement of regret was passed, according to Hoffmann, with which she and Abuzuaiter were personally involved through their work and membership on the city’s Human Relations Commission.Then, after the events in Charlottesville, Virginia, where one person was killed and 19 were hurt after a speeding car drove into a crowd of counterprotesters ahead of the “Unite the Right” rally of White nationalists and other right-wing groups, an apology motion was made. That motion passed 7-1.

Rev. Johnson, who was involved in leading the 1979 march, told CNN that even though the city council issued a statement of regret in 2009, it was unclear what they were regretful for.

“I think there are three things involved in an authentic apology: One is clarity on what exactly you’re apologizing for, two to the best of your ability to say why you think this happened, what was fueling it and three, what is going to be done about it.”

Johnson said these elements were addressed to some degree, but not fully.

“The city has been very reluctant to criticize the police department and if they had actually told the truth right after ’79, many of the police, probably, including the chief would have had to go to court and possibly have been convicted,” he said.

Last year, Johnson formed a group of religious leaders, participants and eyewitnesses to the events of 1979 to meet with members of the city council to craft a resolution.

Last Wednesday, Johnson’s community- based organization, The Beloved Community Center hosted a Facebook Live with survivors and supporters in response to the city’s vote and apology.

“I want us to appreciate the magnitude and the depth of what happened,” he said in the video. “But having said all that, I want to extend my heartfelt gratitude to the City Council.”

The resolution also says that every year, the City of Greensboro will honor and award five graduating seniors at James B. Dudley High School with “Morningside Homes Memorial Scholarships,” an academic award of $ 1,979 in memory of Cauce, Waller, Sampson, Smith and Nathan.

The scholarships will be given to students who submit pieces of an expressive medium, or other forms of expression focusing on racial and social justice issues.

>>>>