But after an ugly, divisive and anxiety-inducing campaign season, Americans are also looking to the future and asking big questions: What comes next? How do we begin our political healing? And how do we restore our collective political voice, without being drowned out by those who shout loudest?

The answer is that we need to update our electoral system — and ranked-choice voting is a promising way forward.

It is easy and emotionally satisfying to cast blame on our current political leaders, and natural to hope that a new group of leaders will somehow be different. It is harder to understand how our political system became so broken, and so distant from the concerns of everyday Americans. But if we want a better future, we must not only assess the character of the people in our political system, but also the rules under which they operate.

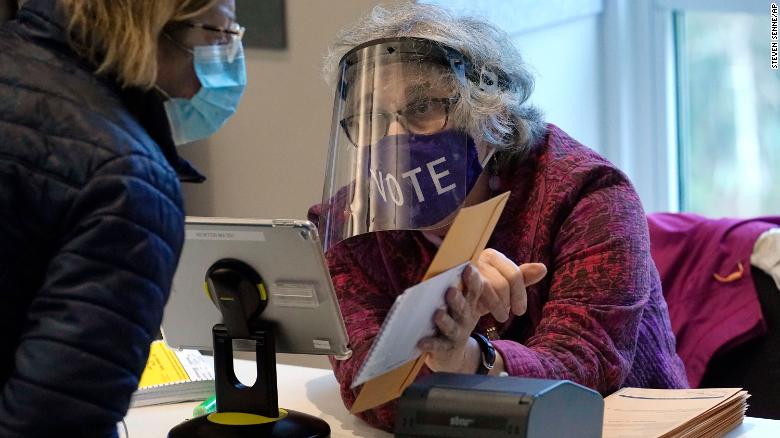

On November 3, something else is on the ballot in both

Alaska and

Massachusetts besides whether Joe Biden or Donald Trump should be president and who should control Congress. Voters there will be deciding whether they want to conduct their future elections under new

ranked-choice voting rules. Though this might seem like a wonky change in process, it is actually a profound step toward a more positive, problem-solving style of politics.

Ranked-choice voting — which already exists for state primary, congressional and presidential elections in Maine and a number of large cities in local elections — is a small tweak to existing voting rules. Under current plurality voting, your ballot offers a list of candidates, but you can only choose one. Most people choose a Democrat or a Republican, because these are the only two parties most people believe have a shot of winning, and so anything else is just a wasted vote, or worse, a spoiler vote that winds up helping the candidate you absolutely don’t want.

Any vote cast as a message of protest — such as one for a third party candidate — comes at a very high cost. And yet, more and more Americans are dissatisfied with and feel unrepresented by the two major parties.

Two-thirds of Americans say they’d like to see a third party. And according to Gallup, the share of Americans identifying as independents has consistently been in the low 40% range

since the mid-2000s.

Ranked-choice voting offers a way out and a way forward. Under ranked-choice voting, you rank the candidates in order of preference. We rank things all the time — it’s as easy as one-two-three. If no candidate gets a majority of first choice votes, the election becomes a runoff, with candidates eliminated from the bottom up.

As candidates are eliminated, no vote is wasted. It is simply transferred to the voters’ next choice until one candidate gets an actual majority of all the votes cast. Requiring candidates to win with a majority of the votes rather than a plurality is hardly a radical idea!

Consider a progressive Democratic voter in 2020 who is less than enthusiastic about Joe Biden, but despises Donald Trump. This voter will almost certainly support Joe Biden. But under ranked-choice voting she could also choose a more progressive candidate as her first choice pick, and if that candidate is eliminated, her vote could transfer to her second-choice pick, Joe Biden. She can express her genuine preference, without wasting her vote.

Though Biden faces no meaningful third party challengers in 2020, Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign faced a challenge from Green Party candidate Jill Stein, and Al Gore’s 2000 campaign faced a challenge from Ralph Nader. In both cases, many Green Party voters would have selected the Democrat as their second choice under a ranked-choice voting election. But without ranked-choice voting, a small Green Party vote bled the Democrats of crucial support in a very close election, helping a candidate who did not win a majority of the vote become president.

And yet, those third-party candidacies also represented something important — a way for Americans dissatisfied with the two major parties to offer new ideas and different visions. Historically,

third parties have been a vital source of new ideas, able to raise issues that either paralyzed — or escape the notice of — the two major parties.

Under ranked-choice voting, more of these new ideas would enter the political conversation. Third parties and independents would no longer be spoilers. Voters could better express their preferences, and send a clearer message. Political leaders would be forced to take note.

Politicians would also be driven to campaign differently, too. Under our current plurality rules, campaigns often play the “lesser of two evils” game, filling the airwaves with negative campaigning that casts the opposing candidate and party as

dangerous,

extreme and

radical, encouraging voters to fear and loathe the other party.

This negative campaigning only works when there is no threat of a third party vote. But there is no phrase “lesser of three evils.” Under ranked-choice voting, the incentives

push candidates to build broader coalitions. A “base first” strategy only works with plurality voting.

In Massachusetts, the vote on ranked-choice voting is likely to be close, but both states are in position where the measure could pass. If Massachusetts and Alaska both adopt ranked-choice voting, expect more states to give a closer look to upgrading their voting systems, too.

And they should. Ranked-choice voting is simply a better way to vote. It gives everyone more choice and more voice. And it encourages candidates to build coalitions and broaden their appeal, instead of pushing division and hatred. If we are going to come together as a nation after this election, we need a voting system that encourages compromise. We need ranked-choice voting.