She saw it coming.

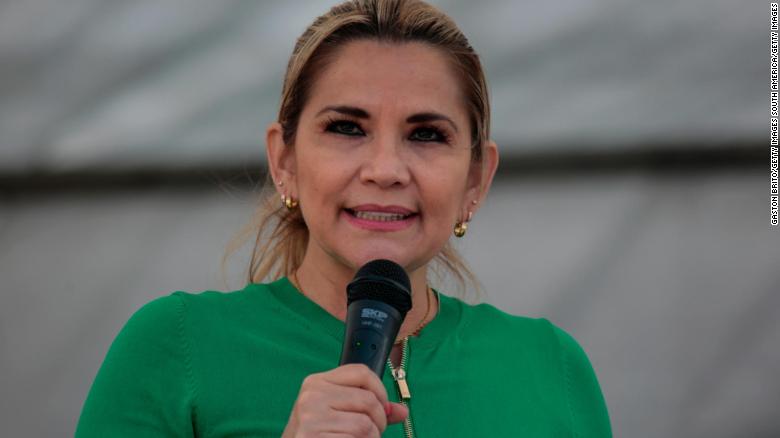

Even before her arrest in the wee hours of the morning Saturday, former interim Bolivian President Jeanine Áñez published several messages on her Twitter account. “Political persecution has begun,” the rightwing politician wrote Friday afternoon. Less than 24 hours later, she would be detained at her home in the city of Trinidad.

Members of her former cabinet were arrested too. Álvaro Coímbra, who served as justice minister under Áñez, and Rodrigo Guzmán, who was her energy minister, were detained as part of a Bolivian police operation apparently targeting officials who served in the previous administration.

“I denounce to Bolivia and the world that, in an act of abuse and political persecution, the MAS government has ordered my arrest. They accuse me of participating in a coup that never happened. I pray for Bolivia and all of its people,” the 53-year-old Anez tweeted just before her arrest, referencing the country’s leftist ruling party Movement Toward Socialism (MAS).

Anez was Bolivia’s interim president for barely a year. Once a little-known second-vice-president in the Senate, she took the job in 2019 amid the chaotic fallout of a disputed election that saw then-president Evo Morales resign and flee to Mexico.

Until that point, Morales had ruled Bolivia for three terms — almost 14 years — and was hoping for a fourth. Though an international audit would later find the results the 2019 election could not be validated because of “serious irregularities,” he declared himself the winner, prompting massive protests around the country.

Then-head of the Bolivian Armed Forces, Cmdr. Williams Kaliman, asked Morales to step down to restore stability and peace; Morales acquiesced on November 10 “for the good of Bolivia.”

But political allies maintain he was removed from power as part of a coup orchestrated by conservatives, including Áñez. After Morales resigned, so did Álvaro García Linera, his vice-president, as well as the senate president and the lower house president, creating a power vacuum that Áñez was constitutionally mandated to fill as a caretaker leader.

The next year, her government organized fresh elections. Luis Arce, a Morales protégé, won, and the former president finally returned from exile to Bolivia.

But now that Morales is back, some fear political vengeance will follow.

Vague charges

Altogether, Bolivia’s Attorney General’s Office has issued arrest warrants against ten officials in the Anez interim government, including the former interim president herself and the two ministers who were already arrested.

The charges are broad and proof scant. According to officials, the charges Ánez and several of her ministers face are terrorism, sedition and conspiracy to commit a coup — accusations they have rejected fiercely, with Anez herself describing the charges as an act of “political persecution.”

Upon his arrest, Coímbra, the former justice minister, said in a video published by Unidad Demócrata, an opposition political coalition, that there was no legal basis for his detention.

“This has no legal validity. Do you know the reason why we are currently detained according to the arrest warrant? It says we have committed the crimes of terrorism, sedition, and others simply because we accepted our posts as ministers. That’s it!” Coímbra said in an impromptu statement made behind the bars of a local holding cell.

Standing right next to him in the same cell was Rodrigo Guzmán, energy minister under Áñez. “This is an illegal arrest. They have detained us on the street in [the city of] Trinidad. They could’ve easily subpoenaed us, and we would’ve gladly appeared in court. We didn’t flee and we won’t do it. We will face this process and all of the political things they may throw at us. We are sure that this is just a smokescreen to hide the terrible management of the pandemic,” Guzmán said.

The government of President Arce, who won the presidential election in October, has denied that the arrests have anything to do with a political vendetta.

Appearing on national TV, Prime Minister Eduardo del Castillo was unequivocal. “It’s very clear that we’re not committing any type of political persecution. We neither act arbitrarily nor intimidate those who think differently. This process had already begun. Justice is taking its course as it is legally proper, and we believe that it has to go on. The justice system has to continue operating independently from whoever is in power,” del Castillo said.

A ‘pushover system’ ?

But international and domestic observers are skeptical that the political and judicial don’t overlap in this case.

According to Roberto Laserna, a Bolivian political analyst, Bolivia’s justice system and security forces are not structured to ensure complete independence and can be easily controlled by the central government. He describes it as a “pushover” system: Though the 2009 constitution stipulated judges should be elected, that has never happened — judges have been designated by the president in power ever since.

“Bolivian democracy is extremely fragile, weak and susceptible to arbitrary manipulation by whoever happens to be in power at a given time. I believe that what has happened with Jeanine Áñez and her [former] ministers is abusive and an affront to the country all those who believe in democracy,” Laserna told CNN.

Accusations of manipulating the Bolivian justice system for political purposes are nothing new in Bolivia. Back in 2009, then-President Evo Morales upon arrival in Venezuela claimed that police forces had dismantled a right-wing conspiracy that planned to assassinate him and his vice-president Álvaro García Linera. Three men holding foreign passports died in a shootout at a hotel in the city of Santa Cruz.

Ten years later, the government of Jeanine Añez dismissed the case, saying it had all been staged so that the leftist government cold target political rivals in the city of Santa Cruz. The prosecutor in charge of the case fled the country in 2014 and is now living in exile in Brazil.

Áñez herself did face accusations of abusing power during her short term. Critics said that the Roman Catholic who brought the Bible back to government proceedings after Morales secularized them was a little too fast to use state security forces to quash indigenous protests around the country. But did she really plot a coup?

Laserna believes such an allegation would be a stretch. Áñez was not in a position of great power at the time of the 2019 crisis, he says, adding that Morales also had put himself into an untenable position by running for yet another term.

“It can be said that Evo Morales felt he was forced to resign. He was indeed forced to resign. That’s evident. People in the streets forced him to resign because he had manipulated justice. He had promised not to run again, and he did. He had called for a referendum which he later ignored. There was a series of acts showing that he was somebody people could no longer trust, and I believe that’s why people forced him to resign,” Laserna said.

José Miguel Vivanco, director of Human Rights Watch Americas Division, has also expressed doubt about the arrests, saying Saturday, “The arrest warrants against Añez and her ministers do not contain any evidence that they have committed the crime of ‘terrorism’.”

“For this reason, they generate well-founded doubts that it is a process based on political motives,” he added.

And another former Bolivian president, Jorge Fernando “Tuto” Quiroga, who governed from 2001 to 2002, has joined the chorus of domestic and international leaders decrying Áñez’s detention.

In a video posted to Twitter, Quiroga suggested that what’s happening to Áñez goes beyond a political vendetta. “With a fable, they’re seeking to change a history we in Bolivia know by heart about what has happened. Sadly, because of the electoral loss, and so that Evo Morales can save face after cowardly fleeing the country [current President] Luis Arce has decided something unheard of in the history of Latin America by criminalizing a constitutional succession,” Quiroga said.

>>>>